ZelinskyMykola

February 6, 1861, Tiraspol, the Kherson Governorate, Russian Empire (now Moldova) —

July 31, 1953, Moscow, USSR (now Russia)

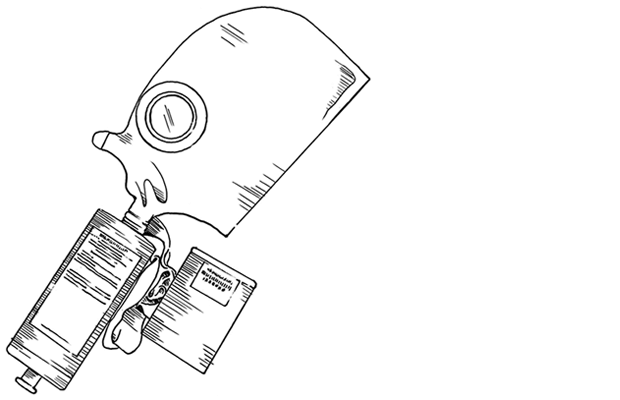

The coal gas mask

The laws and customs of war forbid the use of weapons that may cause unnecessary suffering. But does anyone follow them?

On April 22, 1915, soldiers of the 20th French Corps saw a yellowish cloud moving at them from the German positions. They were sure that the enemy planned an attack under the cover of a smokescreen, so they did not understand what was happening. In fact, the Germans were the first in world history to use a deadly chemical weapon, chlorine.

The chemical attack near the Belgian city Ypres was the first and not the last in that war.

That was when a graduate of the Odesa Richelieu Gymnasium, chemist Mykola Zelinsky, worked in one of St. Petersburg’s laboratories. And as is often the case, solving one problem, he solved another. Working on the production of vodka, Zelinsky was well aware of the property of charcoal to absorb impurities. And then his devoted laboratory assistant Serhii Stepanov received a letter from his son, who fought on the Northwestern Front. In the letter, he shared that only those who put a damp cloth to their mouths, covered their heads with their overcoats, or even laid down and breathed through the loose earth were able to save their lives during chemical attacks.

Then putting everything together Zelinsky realized that he needed to search not for a chemical compound that neutralized deadly gases (at that time, German troops began to also use phosgene in addition to chlorine), but a substance that could absorb them. And the chemist began his series of experiments.

First, the scientist and laboratory assistants moistened birch charcoal with water, put it in a heat-resistant container, covered it with a lid, and roasted it well. So they have increased the number of pores in it several times, and hence the area of absorption. The new coal was called “activated”. So these are the black pills, which today are advised to take in case of poisoning.

Then they found an empty room in the laboratory, which was hermetically sealed, and set fire to sulfur in it. After a while, they entered the room, holding a handkerchief with wrapped activated carbon up to their faces. Under normal circumstances, they would have headaches, nausea, coughs, and fainting, but even after being in the room for about 30 minutes, they did not feel anything like that.

The experiments lasted until June when Zelinsky presented the invented method of protection at a meeting of the gas commission at the Russian Technical Society. At the same meeting, he met Eduard Kummant, a technological engineer at a rubber factory. A few weeks later, Kummant came to Zelinsky with a rubber mask of his design. That’s how the first full-fledged gas mask appeared, a rubber mask and a box with activated carbon screwed to it.

In 1915 a gas mask of the Petrograd model was the first to enter the service. The helmet was put on a rectangular gas mask box with a double bottom, the size of the box was

Despite all the bureaucratic hurdles, sometimes unfair competition, and therefore endless trials that lasted for nine months, until February 28, 1916, Zelinsky and Kummant’s gas mask was finally recognized as the best offered.

In early March, the Chemical Committee ordered the production of the first two hundred thousand gas masks for the front, and later the gas filter with a carbon filter became a military standard. From then on, engineers have been working on its enhancement.

In 1916, five gas masks were sent to London for research and putting into production. The British, who also fought on the side of the Triple Entente (a military alliance between Great Britain, the French Republic, and the Russian Empire), suffered just as much from German gas attacks and sought a way to protect their soldiers.