VasylenkoPetro

October 17, 1900, Migiya village, Russian Empire (now Mykolaiv Oblast, Ukraine) —

April 21, 1999, Kyiv, USSR (now Ukraine)

The theory of rolling a wheel with a trace

One day Petro Vasylenko, a Ukrainian scientist involved in the design of agricultural machinery, received a letter from NASA. And it turned out that agriculture and space are much closer than they may seem. So how did the Ukrainian scientist help the National Aeronautics and Space Administration team, working on a lunar rover for the Apollo 15 mission? First, a little history.

In 1850, the Englishman William Howard designed a locomobile. It was essentially a mobile steam engine to which a plow could be attached, for example, to plow a field, a seed drill to sow it, or a reaper to harvest a crop. Locomobiles were heavy, low power, and more expensive to operate than horses. But in 1862, the first internal combustion engines appeared, and in 1917 Henry Ford began producing tractors of the Fordson model. Farmers appreciated the advantages of self-propelled machines, and for a while, the demand for the tractor exceeded production capabilities. This is where everything started to spin.

Around that time, Vasylenko graduated from an agricultural college, a technical school, and then an institute and entered postgraduate school, where he first researched American combine harvesters and tillage machines. The Soviet authorities made arrangements with American manufacturers to produce machinery under license. For example, in 1924, the Leningrad plant began assembling the Fordson tractor. Vasylenko’s task was to determine which models were most suitable for the conditions of agricultural work in the USSR to put them into mass production. He was also involved in the calculation and design of new farm machinery. In the 1930s, the scientist was invited to investigate how tillage machines affect soil structure because agronomists had long pondered whether this led to its pulverization, compaction, and saturation with harmful impurities. Vasylenko presented the results of his research at the International Soil Science Conference in Paris. Indeed, the use of the technique caused several problems that had to be eliminated.

In 1950, one of his works, “Toward a Theory of Rolling a Wheel with a Trace,” was published. This is what NASA engineers turned their attention to in the late 1960s and early 1970s.

The Apollo 15 spacecraft was being prepared for the flight. In 1971, American astronauts were to land on the Moon for the fourth time and drive a rover across its surface for the first time. Engineers already had more or less an idea of what that surface was like because previous missions had delivered 99 kilograms of lunar soil to Earth. It consisted of fragments of lunar rocks, minerals, and meteorite fragments ranging in size from micrometers to millimeters. The layer of soil was

Crew commander David Scott and lunar module pilot James Irwin rode the rovers 27.9 kilometers. They collected another 77 kilograms of regolith, the name given to the soil of some planets, satellites, and asteroids.

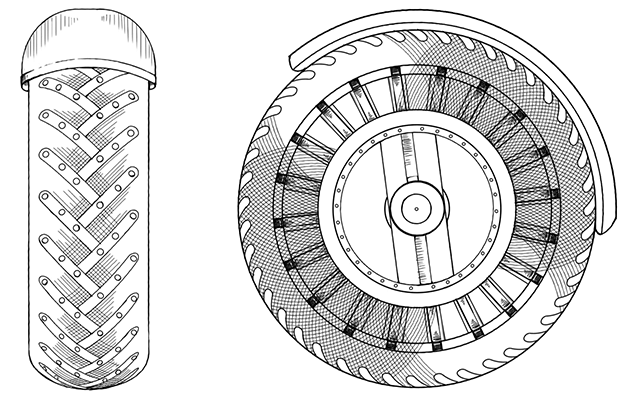

The wheels of the lunar rover from the Apollo 15 mission

Even though the rover occasionally bounced because of the much lower gravity on the Moon than Earth, the astronauts were satisfied with the trip. They said that after reaching maximum speed, they felt safe because the route was designed with all possible obstacles in mind, and there was no oncoming traffic.

In 1972, the identical rovers were sent to the moon on Apollo 16 and Apollo 17. Their design made many improvements, but the wheeling was not changed. The theory developed on Earth by Petro Vasylenko worked flawlessly in extraterrestrial conditions.