TymchenkoYosyp

November 26, 1852, Okip village, Kharkiv province, Russian Empire (now Ukraine) —

May 20, 1924, the city of Odesa, USSR (now Ukraine)

Jumping mechanism

The three most important tasks that engineers had to solve were to turn still photos into exciting films.

The first was solved in the second half of the XVII century, when the device for projecting images on the surface called “magic lantern” appeared. It was probably designed by the Dutchman Christiaan Huygens. A glass with an image on it was placed in the lantern. A candle and lenses, located on either side of the glass, helped to project the image, for example, on the wall of the house, enlarging it several times.

The second problem was solved by the American George Eastman, when in 1883 he released the first roll of celluloid-based photographic film. Eastman founded Kodak company, where in 1889 the Americans Thomas Edison and William Dixon bought a roll of such film for experiments conducted in their laboratory of “live photos”. They cut the film in half lengthwise and thus turned it into the first

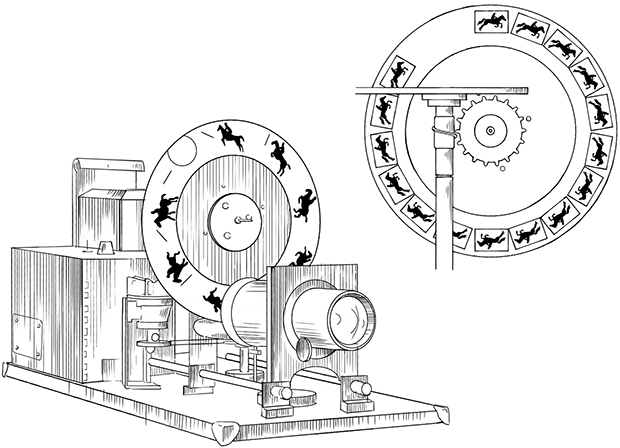

However, the third task was solved by Ukrainian Yosyp Tymchenko.In order for our brains to “revive” a series of sequential images, they must quickly replace each other. It’s like overlapping. What was needed was a mechanism that would not just scroll the film as we roll something at the same speed, but would stop for a while each time the next frame was in front of the camera lens. Scrolled, stopped, scrolled, stopped, scrolled, stopped. And it is important that just when the film is moving, the lens is automatically covered by a curtain so that viewers can see only the change of frames on the screen. For example, a house in the background of which pedestrians and cars will walk. It was this mechanism — jumping — that Tymchenko designed.

Tymchenko was a classic self-taught guy. He was born in a family of serfs, entered the parish school only after the abolition of serfdom. Law of God, church singing, literacy, reading and arithmetic. At this point the official education of the future engineer ended and the stage of practical training began. Today we would call it learning by doing. Fifteen-year-old Tymchenko took a job at Oleksandr Edelberg’s optics and mechanics studio at Kharkiv University. Edelberg not only made binoculars, monocles and spectacles, but was one of the suppliers of Emperor Alexander II, who suffered from myopia.

A few years later Tymchenko moved to Odesa planning to move to America later from there, but fell into the trap of a swindler, lost money and remained in the city with nothing. His engineering talent eventually helped him to get a job as a mechanic at Odesa University. It was the time when dozens of engineers were one step away from finally “reviving” the image. But Tymchenko did not dream about it. Upon the request of one of the professors who had only a scientific interest in moving images he created the “snail” — the first jumping mechanism.

Tymchenko’s film camera and jumping mechanism

Yosyp Tymchenko did not patent his invention, and on December 28, 1895 in Le Grand Café in Paris. Brothers Louis Jean and Auguste Lumiere held the first world-famous film screening. The mechanism of film movement designed by them had a slightly different design, but was also breakthrough.

When at least 12 frames change before our eyes in a second, the brain stops perceiving them separately, and the image «comes to life», but it seems to flicker a little, because next to the frames we have time to notice their absence — the milliseconds when the lens was closed with the curtain.

The flicker disappears if you change not 12 but 24 frames per second. This is because our eye allegedly continues to see the image after it has actually disappeared for about 40 milliseconds. The property is called «inertia of vision», or «persistence».

This time is just enough to not notice the lack of frames.

The movement will look quite realistic if, as advised by Thomas Edison, at least 46 frames per second will change. In addition, the perception of the image at this speed will not strain the eyes.

But the more frames, the longer the film and the more expensive the work on the film.

To show a film lasting 1 minute at 24 frames per second, it was necessary to prepare

In the end the engineers did a trick — they moved the film at 24 frames per second, but covered the lens with a curtain at twice the speed. And although the audience simply saw twice each of the