PulujIvan

February 2, 1845, Hrymailiv, Austrian Empire (now Hrymailiv, Ternopil Oblast (province), Ukraine) —

January 31, 1918, Prague, Austro-Hungarian Empire (now the Czech Republic)

X-rays

In the winter of 1896, fourteen-year-old Eddie McCartney, who lived in Hanover, broke his wrist. Why does anyone remember this more than a hundred years later? Because Eddie became the first guy in America to have an

If you have a color film (red, blue, or green), try looking at the picture through them. Or use for this your smartphone.

When Wilhelm Roentgen spoke on December 28, 1895, about the discovery of

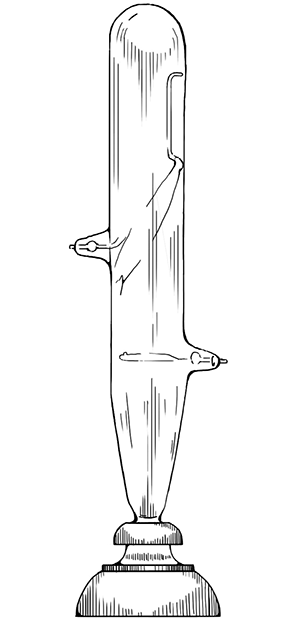

At the end of the 19th century, physicists used electron-vacuum tubes to study the cathode rays discovered in 1859, which occurred in them during the passage of current. In the end, the rays turned out to be a stream of electrons, and the atom was not the smallest particle, as previously thought, but then no one knew anything about it. The tubes were of various designs. In some cathode rays forced the platinum plate to glow red, in others rotated an impeller made of thin sheets of mica.

There were others in which these rays forced the aluminum plate to cast a shadow, and miniature figures covered with metal salts — to glow.

In 1881, Puluj presented several electron-vacuum tubes of his own design at the World Electrotechnical Exhibition in Paris. One of them attracted special attention of the participants and organizers of the exhibition. The light she emitted was bright enough to illuminate the entire room. Because of this it was named “Puluj’s Lamp”. For participation in the exhibition the scientist was awarded a diploma. Puluj later wrote that this light was enough even to read, being at some distance from the “lamp”.

Prolonged exposure to

In the archives of the Puluj family are memories of his wife Catherine-Joseph-Maria, how one day, reading a morning newspaper reporting on the discovery made by

It is said that Puluj sent a letter to Roentgen asking if he had suddenly used his tube, but never received an answer... In fact, it was unlikely him, because the photos taken by Puluj in his laboratory had a much better angular resolution than pictures obtained by Roentgen.

In 1896, both Puluj and Roentgen published almost simultaneously scientific articles explaining the nature and mechanism of action of rays. Puluj’s statements were correct, but Roentgen made mistake.

Puluj’s tube

Roentgen after the discovery of

Some say that Roentgen received the Nobel Prize for their discovery undeservedly, and the rays should not be called roentgen. Others think that Roentgen noticed what Puluj did not immediately pay attention to, so the discovery belongs to him fairly.

All that is known for sure is that Roentgen refused to grant a patent for his discovery, believing that it belonged to everyone. He was also against