LilienfeldJulius

April 18, 1882, Lviv, Austria-Hungary (now Ukraine) —

August 28, 1963, Charlotte Amalie, US Virgin Islands

Field effect transistor

Jews and Ukrainians, Austrians and Hungarians, Germans and Americans consider Julius Lilienfeld their own. He studied with the founder of quantum physics Max Planck, collaborated with the designer of the first airships Ferdinand von Zeppelin, corresponded with the creator of special and general theory of relativity Albert Einstein. He could have won the Nobel Prize if his idea had not been so ahead of its time. However, thanks to this idea, the American Physical Society established the Julius Lilienfeld Prize, which in 1999 was awarded to Stephen Hawking.

The history of transistors dates back to the late eighteenth century, when Alessandro Volt showed that there are substances that conduct current well — conductors, there are those that conduct poorly — dielectrics, and there are those that behave strangely — in one state it conducts well, and in another — bad. These strange substances were called semiconductors and began to be studied. Almost a hundred years later, thanks to them, scientists have learned to equalize the current — to convert AC to DC. And a hundred years later they learned to control and strengthen it. In 1947, three American researchers, William Shockley, John Bardeen and Walter Brattain, who worked at Bella’s laboratory, made the first working transistor.

Why is a Ukrainian here?

For a long time, a team of American researchers could not decide which transistor was the best. Shockley offered one option, but Bardeen and Brattain insisted on another one. Shockley decided to patent his own version of the transistor, because he could not agree with colleagues. He addressed to the patent office and oops... was refused. It turned out that the transistor of the same design in 1926 had already been patented by Julius Lilienfeld. Neither Shockley nor other researchers knew this, because at that time the transistor could only exist on paper, in the 1920s it was impossible to make it, so Lilienfeld recorded the idea, obtained a patent and moved on without giving it any decent publicity.

The Americans eventually patented the Bardeen and Brattain transistor, and in 1956 all three researchers won the Nobel Prize for discovering the transistor effect.

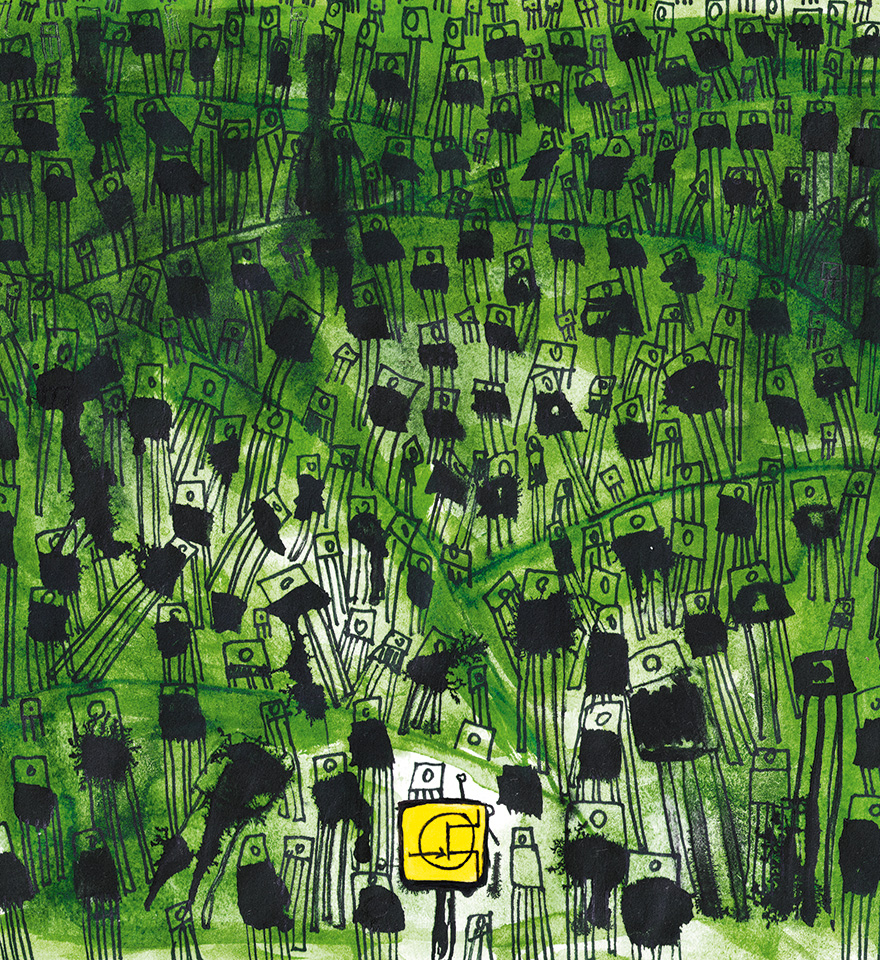

However, it was not possible to establish mass production of transistors of this design. In 1949, every four of the five transistors were defective. So in a few years of trial and failure, production was launched by those that acted on the principle of Lilienfeld. These still make up 99.9 % of all transistors ever made. And many of them have been made and are still made.

Analysts estimate that between 1947 and 2018,

Why were so many transistors made?

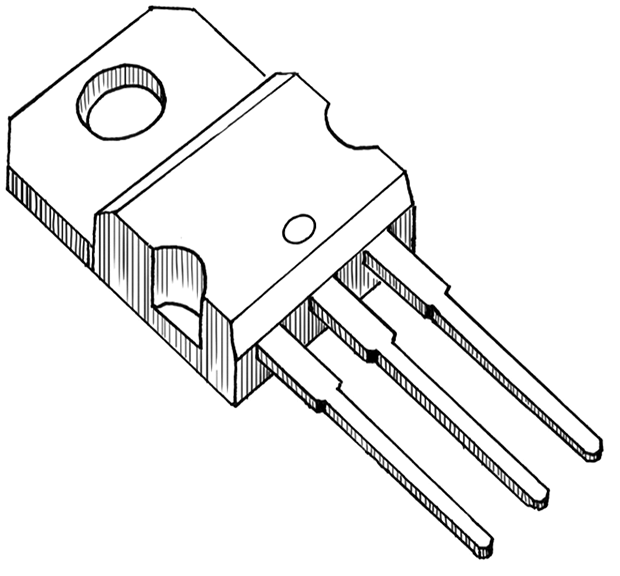

A typical type of transistor

Before the advent of transistors, computers ran on high-vacuum tubes. They occupied entire rooms and often stopped — the lamps burned out and had to be replaced. Although scientists initially saw transistors as an opportunity to improve communication quality (they were the first to install them in hearing aids and radios), in 1971 Intel engineers assembled the world’s first commercially successful Intel 4004 microprocessor from 2 300 transistors. The tiny processor was billions of times better than the then-powerful Electronic Numerical Integrator and Computer (ENIAC), which contained 17 468 high-vacuum tubes, was 2.4 meters high, 30.5 meters long and weighed 30 tons.

That’s where it started!

Each new processor consisted of more and more transistors, and the transistors themselves shrank and shrunk to a few nanometers.

There are about ten billion of them in the processor of a modern smartphone. There are up to sixty billion transistors in computer processors. A 128 Gb memory card can hold more than 100 billion transistors.