FrantsevychIvan

August 3, 1905, Poltava, Russian Empire (now Ukraine) —

February 14, 1985, Kyiv, USSR (now Ukraine)

Protection of gas pipelines from corrosion

Ukraine is ranked fifth in the length of the gas pipeline lines in the world. Their total length is 38 thousand kilometers. Most of these pipelines are called trunk gas pipelines what means that the gas is transported at the speed of 90 km/h and even under enormous pressure, which can reach 7.5 MPa. This pressure is about 30 times greater than the pressure in car tires. If a hole suddenly appears in the main pipe, the gas will not just burst out, it will explode.

The engineers’ task is to protect the pipes from anything that could lead to the formation of the abovementioned holes. For example, from underground stray voltage.

What are these voltages? Why do they stray underground? How does it destroy metal? What should engineers do with all this and what that’s got to do with Ivan Frantsevych?

The history of constructing the first Dashava-Kyiv main gas pipeline in Ukraine will help to find out.

In 1921, the largest for that times natural gas field in Europe the size of which was 12.3 billion m³ was discovered not far from Dashava village, near the Carpathians. Today, Ukraine has barely enough of this stock for half a year, and then it seemed inexhaustible because most companies used coal as fuel. The Dashava-Stryy-Drohobych, Dashava-Zhydachiv-Khodoriv, Dashava-Mykolayiv-Lviv gas pipelines were constructed and that seemed enough for that moment.

The situation changed after World War II. The number of companies ready to work on natural gas has increased significantly, in addition, it turned out that it could be used to cook delicious borscht. It was decided to gasify Kyiv what implied that the trunk gas pipeline should be constructed.

Imagine that someone plugs an iron with a damaged wire into a socket. If the socket is not grounded, someone will get an electric shock, and if it does, the current will go to the ground, because the ground is also a conductor and has a much higher conductivity than a person, and the voltage always goes where the conductivity is higher. And although houses are never built near underground gas pipelines, electricity, straying underground, can come across it. Such voltages from time to time get into the ground from tram rails, construction that provides grounding of electric trains, and more.

When this voltage hits the pipeline, it makes a choice again, but now the conductivity of the steel pipe is much higher, so it penetrates it. This is where the research by Ivan Frantsevych, who worked on the protection of gas pipelines from stray currents, came in handy.

As long as the voltage just moves through the pipeline, there are no threats to it, but somewhere along its path a conductor with even higher conductivity gets on its way, and the current decides to go to the conductor. Going out of the pipe, the current “captures” metal particles and... hello, corrosion!

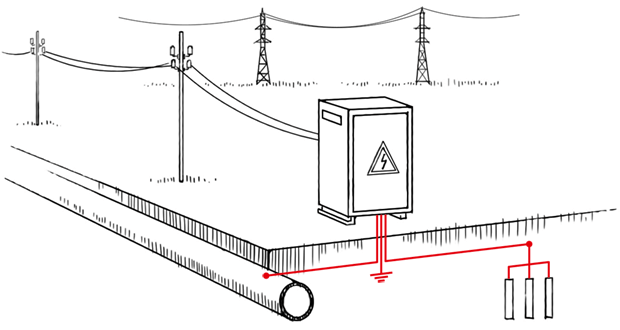

Cathodic protection station. Bottom right — anode ground

To make sure it does not happen, Frantsevych’s engineers began installing cathodic protection stations next to the gas pipeline. Pieces of metal were deliberately buried in the ground, nowadays they have a special construction, and before it could be an old rail or an unnecessary cast iron pipe. When everything was ready, the station was connected to the power grid so that through the cables it supplied a minus to the pipe (cathode) to be protected, and a plus (anode) to a piece of metal. Since the current flows from the anode to the cathode, after the protection was established, the metal particles could no longer leave the cathode tube. And metal particles from the adjacent old rail were moving towards the pipe. So the so-called sacrificial anodes were destroyed instead of a pipe. From time to time they were replaced by new ones.

And what about stray voltages? They are no longer a threat to the pipeline.

The Dashava-Kyiv main gas pipeline was launched on October 1, 1948. Like the deposit, it became the largest in Europe at the time. Its length is 509.6 km long and capacity of 1.5 million m³ of gas per day. Today it is no longer a trunk gas pipeline, but still works, now as a distribution one, delivering gas to villages and cities of Ternopil, Zhytomyr, and Kyiv regions. It will probably work for a long time because all these years the pipes have been well protected from destruction.